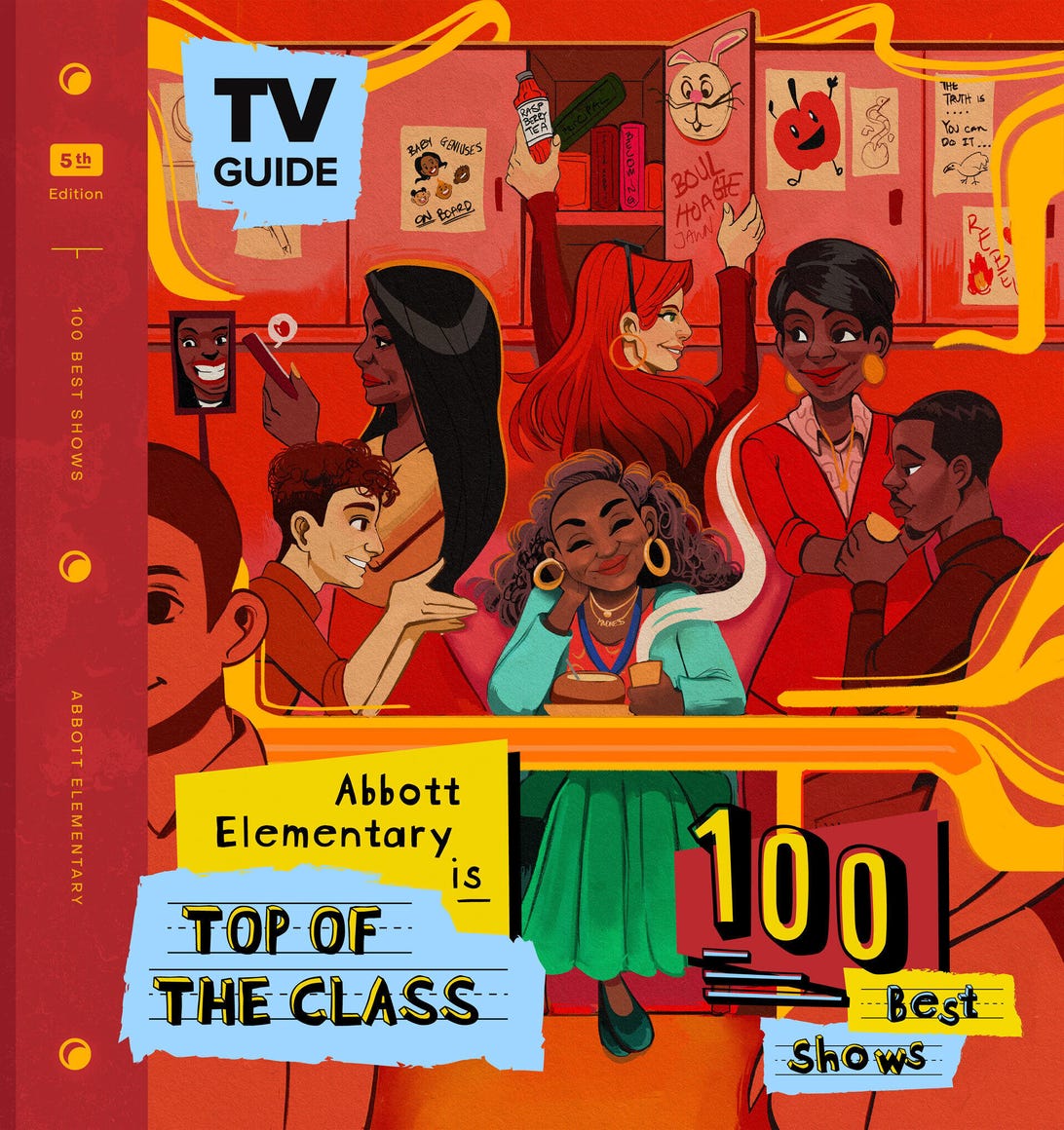

Abbott Elementary Is the Best Show on TV Right Now

The ABC hit is setting the curve for a new school of sitcom. Quinta Brunson and castmates educate us on how the show gets made.

Quinta Brunson had an idea. Before she created Abbott Elementary, her hit ABC mockumentary sitcom, the ambitious 32-year-old writer-actor-producer saw her peers making cable and streaming shows that were hip and timely and won awards but only appealed to niche audiences. No one of her generation had used their talents and taste to make a broadcast sitcom for the masses. But Brunson, who cut her teeth making comedy for the widest possible audience as a BuzzFeed video producer, still believed in broadcast TV. "It wasn't necessarily my intention to make it relevant again," Brunson told TV Guide. "But I did see the opportunity to kind of refresh the medium." Her idea was simple, as most great ideas are: She would make a smart, funny sitcom for everyone.

She saw a wide open space for a show that combined the cultural relevance of shows like Atlanta or Ted Lasso with the family-friendliness of shows she grew up watching, like The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air or The King of Queens. She sensed that people needed a sitcom that felt like the old comedies they loved but was updated to be more inclusive and socially aware – without being preachy about it. Most of all, like everyone else, she just wanted to laugh again.

Abbott Elementary, now between its freshman and sophomore seasons, is revitalizing the network sitcom by shrinking the distinction between broadcast and streaming. A 15-year-old who's never circled upcoming listings in a paper TV Guide and a 65-year-old who doesn't know a Roku from a Grogu can enjoy it equally. It's a traditional television show made by someone who came up on the internet. It feels classic and forward-thinking at the same time. It's the best of both worlds, and the best show on TV right now.

Abbott Elementary's cross-generational appeal became apparent from the moment it premiered. It's a hit on ABC and Hulu, bridging the gap between two different types of viewers with ease. The pilot soft-launched on ABC in December 2021 and topped the 18-49 demographic for its hour. Then it grew its audience in a big way on Hulu, increasing its viewership to 7.1 million watchers in its first 35 days of release. That Hulu boost created buzz when the show premiered in earnest in January 2022, helping it become a bona fide hit, tied with well-established performer The Conners as ABC's No. 1 sitcom. And the show's fanbase is dedicated and vocal. As of March, Abbott Elementary was the most tweeted-about TV comedy of the year so far. If people aren't making memes about your show, your show isn't a hit, and Abbott Elementary has the memes.

The 100 Best Shows on TV Right Now

The show is also a hit in a less measurable but arguably more significant way: People are passionate about it. And not just any people, but cool people like Moonlight director Barry Jenkins, who called Quinta Brunson "the absolute truth," and Donald Glover, the iconoclastic creator and star of Atlanta, who said he was jealous of Brunson for making such a good show within the strict confines of broadcast. America's most artistically ambitious filmmakers aren't in the habit of heaping praise on ABC comedies, but they've taken notice of what Brunson has accomplished. She's made a show on network TV, which is notorious for watering down distinctive ideas, that has stayed true to her creative vision.

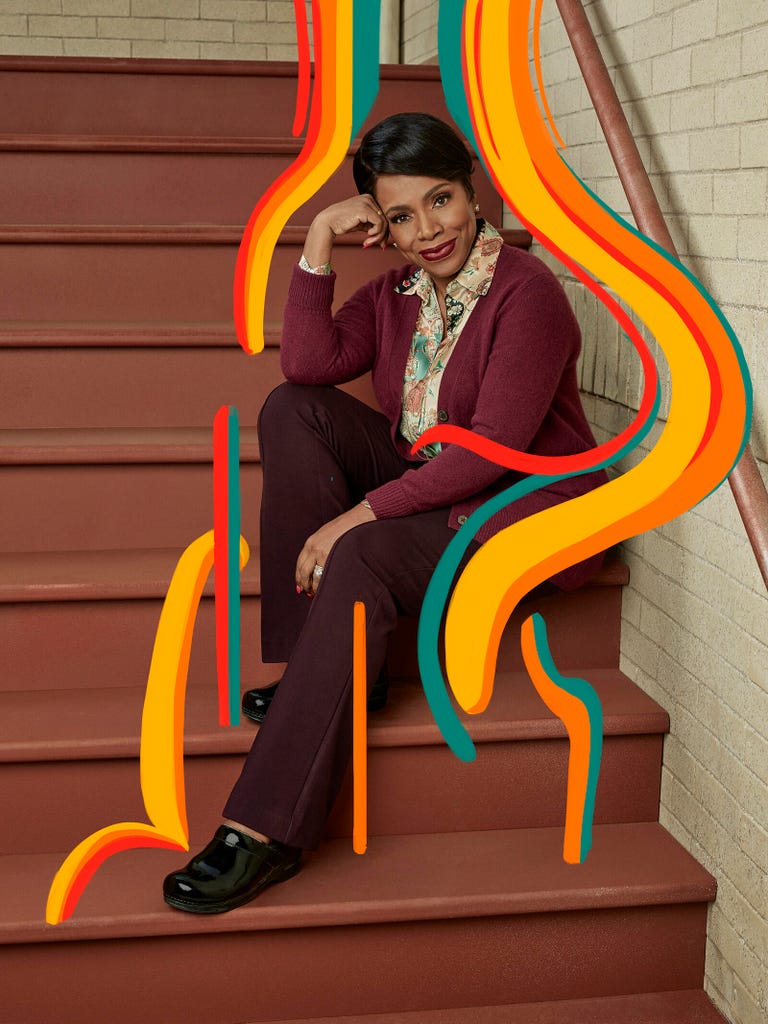

A large part of why the show is resonating with audiences is its authenticity. Brunson's mother was a kindergarten teacher in the Philadelphia school system for 40 years, and the fictitious school itself is named after Brunson's own sixth-grade teacher. According to executive producer Justin Halpern, about half of the show's writers have a family member who's a teacher. Before production on the show started, the producers interviewed everyone from educators to administrators and school board members to school nurses to get a complete picture of what it's like to work in a school. The show's commitment to accuracy speaks to teachers, who see their own workplaces reflected in Abbott Elementary, with its out-of-date textbooks and incompetent administration. Actress Sheryl Lee Ralph, who plays veteran kindergarten teacher Barbara Howard, says she's proud that viewers notice and appreciate her character's comfortable knit sneakers — a popular choice among real-life teachers who are on their feet all day.

Abbott Elementary uses the experiences of schoolteachers to tell workplace stories that become universal through their specificity. Lisa Ann Walter, who plays resourceful second-grade teacher Melissa Schemmenti, thinks that anyone who's had to do more with less can relate. "It's people just trying to make things work when it's not easy and they don't have enough money," she said.

Set in an underfunded public grade school in Brunson's hometown of West Philadelphia, Abbott Elementary follows Janine Teagues (Brunson), an optimistic second-grade teacher in year two of her career. She's contrasted with the school's more experienced teachers, who have learned how to get by with the meager resources the school system provides. The characters are committed to giving their students the best education they can with what they have. But more money would be nice.

On the show, the school is the subject of a documentary about life in financially struggling American schools. Abbott's narcissistic principal, Ava Coleman (Janelle James), invited the cameras in because she's a firm believer that any publicity is good publicity. Much of the show's conflict comes from the teachers having their students' best interests at heart while Ava very much does not. James describes Ava as a layered character who at her core is "a dirtbag who scams kids." But even though Ava gives a human face to the school's difficulties, she's not the show's primary antagonist. The primary antagonist is a lack of resources. "The real villains are the systemic issues that [the teachers are] facing," said Halpern. Ava is just a symptom of a larger problem: a society that would rather invest in just about anything besides leveling the playing field for disadvantaged children.

Abbott Elementary pulls off a difficult feat for any show, let alone a network sitcom. It deals with weighty issues of educational and economic inequality, but handles them with such a light touch that it never fails to be funny. Contemporary sitcom watchers want shows that create a space where the problems of the world can be processed through laughter and camaraderie, and Abbott Elementary does that gracefully.

Chris Perfetti, who plays well-intentioned but terminally corny history teacher Jacob Hill, thinks Abbott Elementary is the right show at the right time. It offers a respite from a constant deluge of bad news. "I think people are really desperate for a place to laugh and maybe let their guard down and celebrate a little bit, and Abbott lets people do that," Perfetti said, "in addition to just hearing things in a way that you maybe haven't heard before, or seeing characters that aren't usually the center of a TV show."

Abbott Elementary stars a predominantly Black cast and is fundamentally grounded in Black culture — one episode revolves around stepping, a dance style rooted in the traditions of Black fraternities and sororities — but it isn't about racial identity the way recent era-defining sitcoms like Fresh Off the Boat and black-ish have been. Brunson always knew that Abbott Elementary was going to handle race differently. "My generation was starting to get tired of race as the only focal point," she told the New York Times in March. "The white shows got to just be white, but a lot of the shows with people of color were about the color of the people and not about stories of the people." With Abbott Elementary, she made sure the focus was on the characters themselves.

She believes her experience making Abbott Elementary is a hopeful sign for other creators of color. "Because of the number America has done on us, a lot of people think they have to bring those identity stories in order to get picked up. But I'm not sure that's necessarily true anymore," she told TV Guide. "I think it's refreshing to just have these stories. And so it makes me want to encourage people to make more stories that are just about the characters."

Abbott Elementary's focus on its characters allows it to weave in social and political issues in a way that doesn't feel didactic or forced — which, as the last several years of television have demonstrated, is extremely hard to do. But politics — actual, material politics about how resources are allocated and to whom, and who is affected by those choices — are part of the show from its very first scene. "I'd say the main problem in this school district is, yeah, no money," Janine says in the pilot's cold open. "The city says there isn't any, but they're doing a multimillion-dollar renovation to the Eagles' stadium down the street from here." The show asserts, over and over and without any ambiguity, that more money should go to public schools.

In the pilot, Janine needs a new rug for her classroom but is told there is no money for one. The story starts in a way that couldn't be simpler or more specific to Janine: her old rug has pee on it, so she needs a new one. She feels the effects of politics on her life — the city is building a new stadium instead of giving more money to the school system — but she deals with those politics by trying to do her job.

"I think that is the more honest way of [exploring] how money, politics, funding, all of that affects people," Brunson said. "It's like, 'You've just made another thing in my day hard, but I don't have the time to do a massive debate about it. I don't have the time to watch a documentary or listen to a podcast about it. It has affected me in this way. I'm gonna mention that and then I'm gonna move on.' I think that's kind of how we approach all of the issues in Abbott, and it winds up working. We try to make [politics] realistic to these characters' involvement with them."

Halpern credited Abbott writer Brittani Nichols for summing up the show's handling of race and politics best. "She was like, the people that are in the game, they know what the game is, and they don't talk about the game," he said. "These teachers who are battling this sh-- every day, they're not sitting around and having flame wars on Twitter about critical race theory and all this other stuff. They're on the ground, doing sh--."

Chris Perfetti's character is a gay man in an era when anti-LGBTQ legislation is making work dangerous for educators like him. Though that legislation doesn't come up in Season 1, the show makes clear where it would stand by taking a matter-of-fact approach to Jacob's sexuality. To Perfetti, Abbott's treatment of Jacob's sexual identity and the recent legislation targeting real-life teachers are two sides of the same coin.

"The world is spinning forward. And as the world spins forward, as we can have characters on TV whose sole function is not based on their sexual identity, I think that really scares some people," Perfetti said. "There is a faction of people in this country, particularly powerful people in political office, who feel like something is slipping away from them. And in my opinion, those things should slip away from them. And so while what's happening in Florida and Texas is devastating, particularly for the young people who live there who don't have any power in that situation, I do think that [characters like Jacob are] this sort of harbinger of what is to come. It's that we're getting close. It's that progress is happening. And there's always a two steps forward, one step back kind of notion when that happens."

In a moment when American politics feel as dark as they ever have, Abbott Elementary is optimistic about American people. It doesn't put on rose-colored glasses — there are difficult problems that can't be neatly solved in 22 minutes — but it finds hope in the idea that good teachers who show up and do the work can make a difference anyway.

Abbott is a socially relevant show, but social relevance doesn't make a show good on its own. It takes an extraordinary amount of care and craft to make a sitcom feel familiar while pushing the boundaries of what's been done before. And according to the cast and crew, the show's quality at every level inevitably comes back to the clarity of Quinta Brunson's vision.

"There's a saying that says people die for a lack of vision," said Ralph. "Well, our series will never die, because Quinta Brunson has vision. Quinta is able to tell you the arc of every character that she has created in this show, the ones that you have seen, and the ones that you will see later on down the line. She, for such a young person, has great depth and wisdom."

"[Quinta] was very clear on what she wrote, who these people were and what the balance was in this ensemble," said Walter. "It just happened to be that what she wrote was perfect for me." Walter organically brought elements of herself into her performance as Melissa, who, just like Walter, is a no-B.S. Sicilian American who has a guy for everything.

Many of the show's cast members were personally selected by Brunson herself, sometimes in nontraditional ways. Tyler James Williams, who plays first grade teacher and Janine's will they/won't they romantic interest Gregory Eddie, was recruited via Instagram DMs. Brunson specifically went after the actors she wanted — people like provocative absurdist comedian Zack Fox, who plays Janine's goofy rapper boyfriend Tariq. The producers needed an actor who understood how to make Tariq likable in his introductory scene, when he's shamelessly mooching off Janine. "We had been having trouble casting that person because I think we knew we had written a very special new archetype," Brunson said. "Everyone who had auditioned was giving us the old version of what they thought it would sound like. And we knew it needed to be a new voice." Brunson thought Fox would be perfect for it, but didn't think she'd be able to cast such a lesser-known, out-there actor on a broadcast sitcom. But with some encouragement from her writers, she texted him about it. Once he auditioned, it was clear there was no one else for the job.

"She became a really good producer," Williams said. "She's always been a great writer. But the way she assembled this cast and runs this show, she's producing at a very high level."

Brunson gets help on the production level from executive producers Justin Halpern and Patrick Schumacker, an experienced writing/producing duo whose job is to help Brunson get what's in her head onto the page and onto the screen. Halpern and Schumacker knew she was a star from the moment they met her four years ago, when she auditioned for a CW pilot they were producing. They could tell she was someone who understood how to zag from what was expected and create a unique and specific character.

The pilot, a sci-fi comedy, was about two girls who work at Chuck E. Cheese who find a crash-landed alien spaceship. "Every other actress that came in, they all played some variation of, like, 'What the f--- is happening here? Oh my God!'" Halpern said. "And Quinta from the start played it just sort of like, 'Is this gonna get me in trouble?'" She got the part, of course. The show didn't go to series, but her relationship with Halpern and Schumacker endured.

To help define Abbott's visual sensibility, Brunson enlisted executive producer Randall Einhorn, who directed six of Season 1's thirteen episodes, including the pilot. Einhorn has directed more than two dozen shows, including multiple episodes of The Office and Parks and Recreation. He is the industry expert on directing mockumentary sitcoms. Abbott Elementary is obviously influenced by both of those earlier shows. It's a workplace mockumentary set in Pennsylvania with romantic tension between a Leslie Knope-esque eternally optimistic striver and a deadpan, job commitment-hesitant Jim Halpert type of guy. Brunson is open about the earlier shows' influence. "I knew I wanted Abbott to live somewhere between the two," Brunson said. "We talked a lot about that in the beginning. Since there's only so many mockumentaries in American television, we knew we were operating between the spaces of the two main ones on broadcast TV." But Abbott Elementary has a soul all its own, more visually bright and colorful than The Office and less caricatured than Parks and Recreation. Brunson worked with Einhorn — who before he became a director was The Office's director of photography — to develop Abbott's unique visual identity.

A lot of the differences between Abbott and the earlier sitcoms are subtle ones that viewers might not notice on their own, but that do a lot to define Abbott's tone. On The Office, Einhorn explained, the talking head interviews were usually conducted in front of a window or a wall, creating a claustrophobic feeling. On Abbott Elementary, they're usually in a hallway that extends past the edge of the frame, giving the show a feeling of openness. Abbott doesn't have the cold, bland blues and grays of The Office because the interview cameras are outfitted with vintage lenses that make the scene look warm. They shot the pilot in a school in Los Angeles, and Einhorn didn't like the clinical feel of the metal windows in the classrooms, so he had wood put over them to make them look older, like students had been opening and closing them for generations. "We wanted it to feel warm and lived-in, but also tired," he said.

Einhorn said the look of the show reflects the respect the show's writing has for teachers. "These caregivers and these nurturers of our children, they're heroes," he said. "So I really wanted them to look good."

Brunson said the way characters interact with the cameras gives viewers insight into who they are as people. "Barbara, for instance, doesn't really do to-cameras that much because she's not someone who has that much time to talk to the camera," she said. "But Janine wanting to overcompensate and be in the camera's face all the time is a part of the nuance of her being a new teacher who's learning the ropes."

The show is shot in a way that's typical for mockumentaries but atypical for other types of sitcoms. There are three cameras going at a time, capturing everything in a scene, and the actors don't necessarily know who the camera operators are looking at. The whole set is fully lit so that the crew doesn't have to keep resetting based on which direction the camera is facing. This means setting up the lighting takes longer than it usually does on sitcoms, but the actors do fewer takes of a scene (usually only five or six) because everything is being captured at once. Filming this way keeps shooting days short and actors' performances fresh and organic. Brunson recently filmed a guest appearance on Starz's upcoming Party Down revival, and she jokingly commiserated with star Adam Scott, previously of Parks and Recreation, about how mockumentaries had spoiled regular TV for them.

The cameras, and the people operating them, are characters on the show, too. They work with the actors to help create the spontaneous style of comedy unique to mockumentaries. Williams said that his signature to-camera reaction shots are not in the script, but rather come out of in-the-moment collaboration with camera operators during filming. Over the course of the season, the actor built a shorthand and rhythm with each camera operator. As they got to know him, they learned to anticipate when he was about to throw them a look, and they were there to catch it. "Them being able to feel me about to do it is really incredible," he said. "That's a skill that I don't think most people realize." They're improvising with a camera in their hands.

Dialogue, on the other hand, is rarely improvised on Abbott Elementary because it's so good as written. But occasionally some improv makes it into the finished product. Barbara Howard's line "Sweet Baby Jesus and the grown one too" came from a private joke Sheryl Lee Ralph had with a friend that she brought to a scene where she was instructed to come up with her own line. Janelle James recalled a time she punched up a line — "She pale like a zombie! You know, they eat the hottest people first. Let me back my tasty ass up" — and Quinta Brunson, who was lying on the floor, popped up to ask if she heard correctly that James just said "tasty ass," then said, "That's funny," and lay back down.

As the showrunner, Brunson works hard to treat everyone who works on Abbott well. Multiple people involved in the show mentioned that she knows everyone's name on set. To her, it's a given that she would know the name of everyone who works on the show, because they're all integral and dedicated to making it. She chooses to lead from a place of kindness and hopes that it trickles down to everyone who works on the series.

Kindness permeates the show, down to the wardrobe choices. Brunson worked with costume designer Susan Michalek to pick out specific pieces that communicate something meaningful about the characters, and her character always wears a necklace that says "kindness."

"One of the specifics for Janine was, that's what Janine believes in, above all, is kindness," Brunson said. "And even on her worst days, she's still wearing that necklace."

Abbott Elementary's success means Hollywood is going to want Quinta Brunson to produce other shows and be in movies and spread her magic around, which could make it difficult to devote as much time and energy to Abbott. "I'm terrified of the day when she goes away," Lisa Ann Walter said. But Brunson doesn't want to get pulled away from her creation. There's a lot of pressure in the industry for successful creators to build an empire of shows, but she's only focused on Abbott right now. And she wants to continue doing only the things she really wants to do. "I would like to keep operating that way. That feels very healthy to me," she said.

Abbott is ahead of the curve on what's coming next in TV comedy. Netflix, the entertainment industry's most influential streaming service, is moving away from the dark "sadcom" dramedies that defined the previous era of TV comedy and is instead looking to make broadcast-style sitcoms. Audiences and network executives alike want new comedies that feel like classic sitcoms, but are kinder and more engaged with the present moment. The future of TV comedy will take pieces of its past and build something new with the parts.

Abbott Elementary is already there.

To celebrate Abbott Elementary as the Best Show on TV Right Now, TV Guide readers and Abbott Elementary fans are teaming up to support real teachers and the essential work they do in schools across the country. TV Guide will proudly match the first $5,000 in donations. Learn more and donate here.

Illustrator: Cora Jaeschke

Art Director and Designer: Justin Vachon

Project Editor: Kelly Connolly